‘COVID Cases Coming From Small Villages… Monsoon Fevers Confounding Situation’

Chennai: India has crossed the 5 million mark for COVID-19 cases and recorded more than 83,000 deaths. While data are available for the national and state levels and for some districts, the situation elsewhere, especially in towns and villages, remains largely opaque.

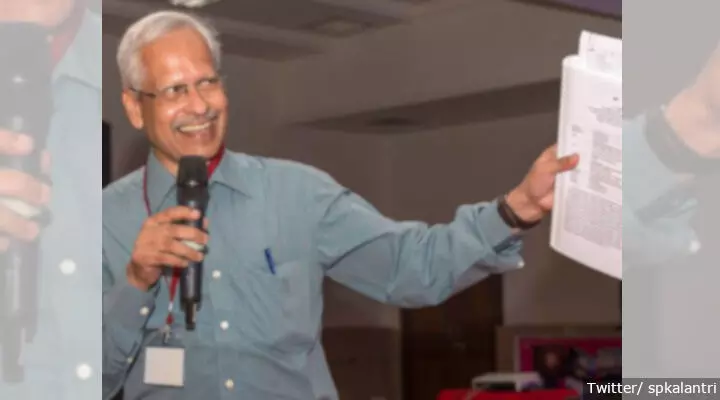

S.P. Kalantri is the medical superintendent at Kasturba Gandhi Hospital in Sevagram, in eastern Maharashtra’s rural and backward Wardha district, and has been professor at the attached Mahatma Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences for over 30 years. He spoke to Rukmini S. about the view from Wardha on the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19.

He says cases are starting to come in from villages. Wardha district has two labs that can conduct RT-PCR tests, and together are doing close to 400-500 tests per day. “Suddenly, we have found that the proportion of people testing positive has now grown to 40% each day,” he says. All patients are being taken to COVID-care centres or hospitals, since “given our social structure and small homes that lack individual bedrooms and bathrooms, it is impossible to give people the luxury of being confined in their homes”.

Edited excerpts:

When we spoke earlier in the year, you talked about a feeling of waiting and watching. And now Wardha is reporting over 150 cases each day. So it seems like the time has now come for Wardha?

On May 10, our Wardha district in eastern Maharashtra recorded our first case. The months of May and June were relatively OK--we had a small number of patients coming, and we were able to cope with them. But in the last several weeks, we saw a sudden surge in the number of COVID-positive individuals.

Right now in my hospital, which is in a small village called Sevagram, there are 175 COVID-positive patients; 27 of them are in the ICU and a dozen of them are on mechanical ventilation. Every day, our Wardha district is recording between 150 and 175 new cases, and it looks like these cases are now coming from smaller villages also.

From the patients who are coming to you, do you have a sense of where they are contracting the infection from?

I think it’s definitely community transmission. By community transmission, we mean that we don't know where this infection is coming from and from whom. People are coming from smaller villages, smaller towns, those who have never travelled. Suddenly we are seeing that all over the small villages which are located near Sevagram, now men, women, children, pregnant women, old people, people with comorbidities, they are coming.

Were the people coming from small villages aware of the disease before it struck them?

Yes, there was a fair degree of awareness, probably thanks to the fact that almost everybody now has a smartphone. When I talk to people coming from the small villages of our catchment area, I do find that almost everyone is aware that there is a new virus, it is likely to be a lethal one, it is not as benign as our common cold, it is something different from malaria or dengue. They are also aware that there is no remedy for the virus.

How are cases being discovered in general?

Those who come to the hospital and have symptoms suggestive of COVID-19 undergo testing. Similarly people who are admitted to the hospital and have got lung involvement also get tested. All pregnant women who are nearing their term get tested. People who are scheduled for routine surgeries are tested if they have symptoms or are at high risk for COVID-19.

The district hospital has a contact-tracing, testing and isolating protocol and the district administration also finds some cases. Right now, Wardha district has two labs that can do RT-PCR tests and both put together are doing close to 400-500 tests per day. Suddenly we have found that the proportion of people testing positive has now grown to 40% each day. By 9.30 every night, our labs report the test results, they are quickly communicated by email to the district health authorities.

The health authorities have patients’ phone numbers and addresses and pick them up. If they are asymptomatic, they are put in COVID-19 care centres. If they have symptoms, are elderly or have comorbidities, they are admitted to a dedicated COVID-19 care hospital. There is our medical college, and another one with around 1,000 beds, and between us we admit 60-80 new cases every day. There is no home quarantine right now; given our social structure and small homes that lack individual bedrooms and bathrooms, it is impossible to give people the luxury of being confined in their homes.

In the two hospitals, is infrastructure and manpower adequate?

Fortunately, until now, we haven’t faced problems. But now that we are six months into the pandemic, fatigue has started setting in among healthcare workers. There is burnout syndrome as well. And as quite a few healthcare workers also have got infected, there is now a fair amount of fear and panic among healthcare workers as well. We spend a lot of time allaying their fears, motivating them, identifying their problems and helping them cope with newer and newer challenges that the illness is breeding. Probably as more and more cases come--and we all feel that the worst is yet to come--it will be a hugely challenging task for all of us to ensure that we have adequate human resources. Working in a COVID-19 ward is extremely difficult and every day we have to design innovative solutions to make sure that our healthcare workers stay motivated, their contribution is properly acknowledged, and when they go home, it should be with some sense of satisfaction.

Our national health data show that rural populations have a lower prevalence of the kinds of non-communicable diseases that are comorbidities for COVID-19. Are you seeing any difference in the way cases are presenting to you compared to your peers in big cities?

Compared to the urban population, yes the prevalence of lifestyle diseases like diabetes, high blood pressure, heart problems is definitely on the lower side in the rural population. But the problem is in the last decade or so, we have seen a sudden surge in these lifestyle problems in rural areas also. It’s possible that if every fourth Indian who is living in a city and is more than 40 years of age has high blood pressure, it would be probably one in six so far as rural areas are concerned. Of the total 760 admissions that we have had thus far, close to 40% had comorbid conditions--either high blood pressure or diabetes, or heart diseases or kidney problems.

When we spoke earlier, you had expressed worries about the fever epidemics that sweep rural areas in the monsoons. How is that playing out--is that creating challenges especially in terms of testing?

Yes, it is another challenge. It’s what we call the monsoon fevers, and every year we have our share of the top five disorders--malaria, dengue, chikungunya, leptospirosis and scrub typhus--and the story is repeating itself. That is a huge challenge. To give you some numbers, every day we see 1,600 patients in our outpatient department, of which 20-30% come with fever or fever-like symptoms. It is extremely difficult and challenging given the sheer numbers, given the lack of proper and reliable diagnostic tests and given the fact that in large public hospitals, it is nearly impossible to segregate non-COVID patients from COVID patients. Every day, we face this problem that people who got admitted to a general ward with a suspicion of dengue or malaria turned out to be COVID-positive. Or a person who had a stroke or heart attack, or was scheduled for surgery and didn’t have any symptoms turns out to be COVID-positive when tested as part of pre-op assessment.

This creates a huge amount of confusion and panic in the system among the healthcare workers treating them, even though we teach them that every person should be assumed to be COVID-positive unless proved otherwise. Given our facilities--old buildings, old infrastructure--it becomes extremely difficult for them to protect themselves and reliably distinguish non-COVID illnesses from COVID.

Lastly, again when we spoke earlier, you had expressed concerns that when restrictions lifted, people with chronic conditions were likely to present with far more degenerated forms of their illness. Are you seeing that happening now in your OPDs?

Unfortunately, my prophecy has turned true. We are seeing a lot more patients with an advanced heart disease, people who could have benefitted from an angioplasty or a bypass surgery, had we addressed their problems three or four months earlier, now coming with a situation where they cannot be operated upon. We are seeing patients with cancer who probably were in stage 1 or stage 2, but now their cancers have advanced, or their immune systems have gone down, or they are not fit enough to get operated for their cancers or undergo chemotherapy. This is occurring across the entire spectrum of healthcare that we provide. Often we feel very sad, angry and disappointed that these individuals could have been given proper healthcare, many of these complications could have been averted, and we could have sent them home in a much happier frame of mind.

But unfortunately we lost that opportunity in the last couple of months because of several reasons. The hospitals were operating at sub-optimal potential, there were lockdowns, people were not able to access healthcare services and people were also fearful of visiting hospitals. Now we are seeing their diseases in more malignant and advanced forms presenting to us.

(Rukmini S. is an independent data journalist based in Chennai.)