Understaffed, Underserved: Human Problems Of India’s Public-Health System

On August 15, 2016, in his Independence Day address, Prime Minister Narendra Modi promised a safety net of up to Rs 100,000 for families who lived below the official poverty line. This programme, however, may do little for people who lack access to qualified medical personnel.

Up to 62% of government hospitals don’t have a gynaecologist on staff and an estimated 22% of sub-centres are short of auxiliary nurse midwives (ANMs)--together, gynaecologists and ANMs are the frontline of the battle against infant and maternal mortality--according to our analysis of District Level Household Survey (DLHS-4) data. At the same time, health facilities are fewer than required, which means that the actual shortfall in personnel is much higher.

Our other findings:

- In 30% of India's districts, sub-centres with ANMs serve double the patients they are meant to.

- As many as 65% of hospitals serve more patients than government standards require; the number rises to 95% if we include hospitals with a gynaecologist on staff.

- Almost 80% of all public hospitals serve twice the number of patients that government standards specify.

Consider these statistics in light of India’s slow progress in reducing maternal and infant mortality. Despite the fact that eight in 10 babies were born in hospitals in 2011-12, up from 41% in 2005-06, according to government data, India continues to have the highest rate of infant mortality among BRICS nations, as IndiaSpend reported in May 2016.

From 256 women who died per 100,000 live births, according to National Rural Health Mission (NHRM) surveys in 2004-06, India's maternal mortality rate (MMR) improved 30% to 178 deaths per 100,000 live births by 2011-12, but this is worse than countries in the neighbourhood, such as Sri Lanka (30), Bhutan (148) and Cambodia (161), and worst among the BRICS countries: Russia (25), China (27), Brazil (44), and South Africa (138), according to the World Bank’s latest estimates.

More money, more health sub-centres over 10 years, but where are the staff?

The NRHM was launched in 2005 to provide affordable healthcare in rural areas, improve healthcare quality and reduce maternal and infant mortality. In 2013, the mission was rebranded as the National Health Mission (NHM) with two components, NRHM and National Urban Health Mission (NUHM).

The budget for NRHM in 2005-06 was Rs 6,713 crore, which rose 67% to Rs 11,196 crore in 2015-16. And, through the roll-out of Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana (RSBY) insurance program in 2008, the government of India has demonstrated a concerted effort to help the poor pay for medical expenses.

But, even as the number of sub-centres rose 5%, from 146,026 in 2005 to 153,655 in 2015, according to Rural Health Statistics (RHS) data, a critical element of the public-health system continues to falter: There aren't enough doctors and nurses.

Our analysis of India’s District Level Household Survey (DLHS) data reveals that a large proportion of healthcare facilities across India don’t have the required number of trained medical personnel on staff, creating impossible caseloads for those on duty. This problem is most pronounced in public hospitals and rural areas, which serve the most vulnerable Indian citizens.

Absenteeism matters—but so do vacancies

Much has been written about absenteeism amongst public sector employees and its impact on basic public services, including its impact on the quality of health services (here and here). The absenteeism rate across the public education and health sectors in India was 40%, tying with Indonesia, according to this 2006 study conducted across primary schools and primary health centres in six countries.

Much less attention has focused on the vacancies in public-sector employment and especially the public-health system. While the number of healthcare facilities across India has increased substantially, as we indicated, the count of medical personnel has not kept pace—and rural facilities have the largest gap between the supply and demand of basic health services, as measured by vacancies.

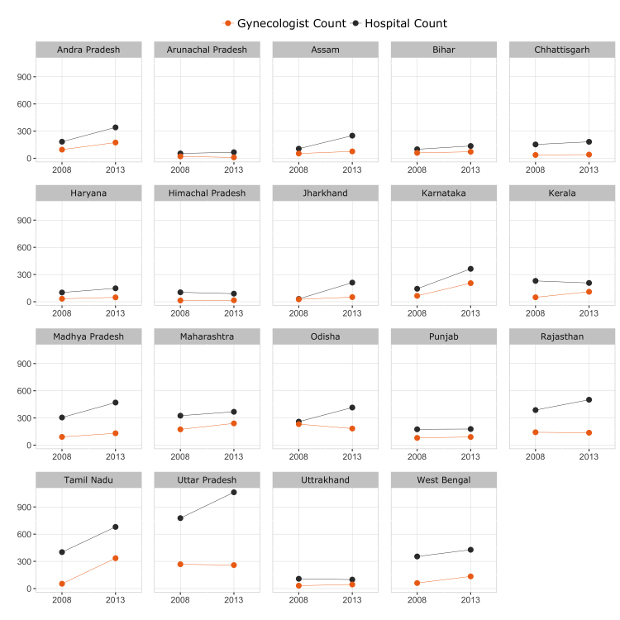

Since the launch of NRHM, two rounds of DLHS (round 3 in 2008 and round 4 in 2013) have been conducted which highlight the staffing gaps in maternal and child health.

Gynaecologists play a crucial role in ensuring safe and healthy pregnancies and deliveries. Even with the increase in the number of facilities nationally, the number of practicing gynaecologists has not increased significantly. In 2008, the number of government hospitals--including CHCs, sub-district hospitals (SDHs) and district hospitals (DHs)--was 4,423, of which only 1,633, or 37%, had a gynaecologist. In 2014, the number of hospitals rose to 6,318, but only 2,409, or 38%, had a gynaecologist.

In short, DLHS-4 indicates that close to 62% of hospitals do not have a gynaecologist on staff.

The government finds it hard to meet its own standards

The government of India increased funding to the health sector through NRHM and put out the India Public Health Standard (IPHS) in 2007 (updated in 2012) which prescribes healthcare standards for facilities and personnel.

These updated standards aim to address the shortfall in doctors and other staff in public-health facilities. There should be at least one sub-centre per 5,000 people, and each sub-centre should have at least one ANM on staff, according to IPHS standards.

Similarly, IPHS prescribes one CHC per 120,000 people and one gynaecologist per CHC. As per these norms, India needs more than 10,000 gynaecologists in its public-hospital system. However, according to RHS data, there are only 3,429 sanctioned posts for gynaecologists across the country, of which only 1,296 have been filled. In other words, if we use IPHS as reference, CHCs have no more than 12.6% of the gynaecologists they should. This number increases if we only assume the number of sanctioned posts as benchmark.

The map shows spatial variations in the percentage of vacancies and population served per facility with the required personnel on staff. The map provides district-level information on the percentage of facilities without an ANM or gynaecologist, as well as the population served by each of these workers. (These figures exclude Gujarat and Jammu & Kashmir, for which DLHS-4 data have not been released.) ANMs are India's bulwark against maternal and infant mortality: For any lower-level health facility, such as the sub-centre, an auxiliary nurse midwife is the first point of contact for pregnant women seeking healthcare. Yet many sub-centres remain without an ANM, and the majority of hospitals still do not have a single gynaecologist.

The histograms show district-level estimates for average population per facility. In the case of sub-centres, only 143 districts, around 25% of the total, comply with the IPHS standards by having centres serve an average population of 5,000 or less. In fact, more than 15% of the districts have an average population per facility above 10,000 people, more than twice the IPHS limit. In the case of sub-centres that have ANMs on staff, only 20% of the districts comply with the IPHS population limit and more than 30% of the districts have more than twice the IPHS population limit. The distribution is even more skewed for hospitals. Only 35% of the districts comply with the IPHS standards; that number drops to 5% when we limit the sample to hospitals that have a gynaecologist on staff. And within that 5% of districts with gynaecologists on staff in their hospitals, 420 districts—almost 80% of the total—have average population per hospital which is more than twice the IPHS population limit.

The deficit of health workers in the current public-health system is clear.

In the public debate over how to ensure high-quality public services for all Indians, vacancies must stand alongside absenteeism as a critical area for improvement. Until these vacancies are filled, infrastructure investments and financial safety nets will fall short of ensuring adequate access to quality healthcare for the poorest Indians.

(Mittal is a Research Associate for Evidence for Policy Design (EPoD) India at IFMR. EPoD India works on a variety of research-policy partnerships aimed to bring insights from data and research to bear on public-sector policies. Singh is a Research Manager for EPoD India at IFMR.)

We welcome feedback. Please write to respond@www.health-check.in. We reserve the right to edit responses for language and grammar.

__________________________________________________________________“Liked this story? Indiaspend.org is a non-profit, and we depend on readers like you to drive our public-interest journalism efforts. Donate Rs 500; Rs 1,000, Rs 2,000.”